July 19, 2013 | Although he has a real-life story of relatively recent vintage to tell in Fruitvale Station – one that, in light of the Trayvon Martin killing and its frustrating aftermath, is enthrallingly relevant to our times – writer-director Ryan Coogler chooses to begin his exceptionally accomplished debut feature with a storytelling device that recalls, of all things, classic film noir of the 1940s and ‘50s.

Borrowing a page from such fatalistic melodramas as D.O.A., Detour and Double Indemnity, Coogler begins more or less at the end, when his lead character’s fate is irreversibly sealed. Then Coogler proceeds to detail the events that took his protagonist to this point, retracing his steps in such a way that – because we know what awaits him at the end – the journey feels less like a series of arbitrary incidents than a riveting progression toward a tragic inevitability.

For the makers of film noir, this sort of narrative structure served well to enhance the suspense as their anti-heroes were methodically undone by poor judgment, cruel coincidence, or both.

But Coogler has a different aim.

In the opening minutes of Fruitvale Station, the filmmaker backhands us with eyewitness video of an actual killing that occurred in Oakland, California, during the early hours of New Year’s Day 2009. We see Oscar Grant, one of four young African-American men detained by BART police officers, lying on his stomach, unarmed and handcuffed, when he is shot in the back by a white cop.

Then the cellphone-captured footage gives way to fact-based dramatization, and the narrative jumps back 24 hours, so that Coogler can show us the final, fateful day in the life of a man who has no idea what a terribly unjust quietus awaits him.

And because we know how that day will end, we can’t help responding to each scene that unfolds with varying degrees of pity, fear and helpless, hopeless, slow-burning anger.

Please don’t misunderstand: Fruitvale Station is not a simplistic story about a slaughtered innocent. Coogler is too intelligent and truthful a storyteller to try stoking our outrage by deifying Oscar Grant. Instead, he presents the unfortunate young man as recognizably human and undeniably flawed, unhappy about his past and uncertain about his future.

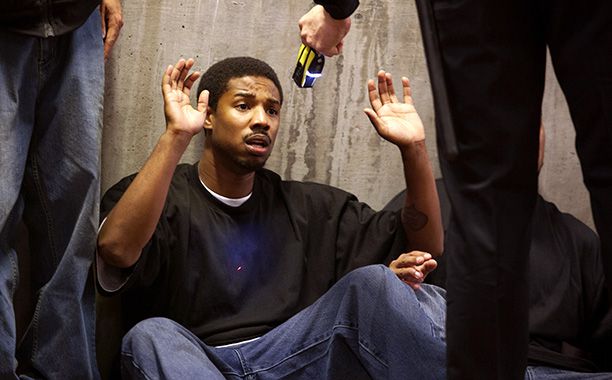

Played affectingly but unaffectedly by Michael B. Jordan (of TV’s The Wire and Friday Night Lights), Oscar is a 22-year ex-con who wants to quit his small-time drug dealing — but maybe won’t, or can’t — and occasionally cheats on his lovely Hispanic girlfriend, Sophina (Melonie Diaz), the mother of his young daughter, even though he appears to genuinely love her.

He’s reflexively helpful to a young woman he meets at the food store where he used to work, to the point of calling his grandmother to give her some cooking tips. But then he runs into his former boss, and the confrontation very nearly turns ugly as Oscar, barely able to contain his fury, learns there’s no way, absolutely no way, that he’s getting his old job back. At that point, you can’t help wondering whether his chronic tardiness wasn’t the only reason he got fired.

At another point, there’s a flashback to Oscar’s prison stretch – specifically, a recollection of a visit from his loving but not infinitely patient mom, Wanda (Octavia Spencer, whose performance is an achingly precise thing of beauty). The conversation starts off amiable, if slightly strained, then erupts into angry recriminations, and ends with Wanda departing in a huff, and a suddenly vulnerable Grant crying out, in vain, for her embrace. (His plea is echoed in a later scene that has the impact of a gut-punch.)

The good news: Oscar and his mother obviously went on to patch things up, because he’s eager to celebrate her birthday — on New Year’s Eve — at a family gathering that is by turns warm-hearted and wryly funny, and occasionally both at the same time.

The bad news: When Oscar says he and Sophina are going over to San Francisco to watch fireworks and party hearty, Wanda worries about his possibly driving while intoxicated – so she makes him promise to go there and come back on the BART.

And so it goes, one seemingly unrelated event interlocking with the next, moving steadily, relentlessly, to the final destination. Coogler plays the role of the unobtrusive observer, so that Fruitvale Station often has the flavor of a cinéma vérité documentary as cinematographer Rachel Morrison nimbly employs a hand-held camera to achieve compellingly persuasively degrees of intimacy and verisimilitude. (Much of the movie was shot in the Bay Area neighborhood where the real Oscar Grant once lived.)

Only one scene, involving a singularly unfortunate dog, comes across as too suggestive of schematic contrivance, or too obvious in its loaded symbolism. Otherwise, naturalism is the keynote of this low-key stunner. There is a frightful lurch from serendipitous camaraderie to steadily mounting conflict and chaos in the climactic scenes. But the very abruptness of the brutality is part of what makes it all too believable.

And in the end, as the lights come back up and you slowly rise from your seat and head for the lobby, you may find yourself charged with alternating currents of profound sorrow and seething rage as you contemplate this story – and, yes, other stories like it.